Ukraine war part 4 - Ukraine's counter offensive.

Understanding

Ukraine’s counteroffensive

As I am not a military man, I would hesitate to comment on

an actual battle, not just due to lack of subject matter expertise, but because

there would be many who can do a better job of explaining military operational

art. My posts on the Ukraine war have been either on grand strategy, or

commenting on certain parameters, based on open-source data, where I think they

are important indicators of how the conflict will pan out and there is no

single article I have read that provides a good explanation.

In this context, the Ukraine counter offensive (CO) which started on 4th

June has also not had analysis which looks at numbers and overall strategy to

explain what is happening on the ground. Most Western reporting echoes press

releases from the Ukraine Ministry of defense and reflects what the writers

would ideally like to see happen, while Russian posts talk of heavy Ukrainian

losses to a point where they are not credible. After going through telegram

channels and media from both sides, incl. Russian, here is my attempt to

explain the counter offensive, with the relevant numbers:

Background: Ukraine carried out successful offensives

in Sept 22, that saw the Ukrainian army retake about 6000 Sq km of territory in

Kharkov region and the Russian withdrawal across the Dnieper in the Kherson

region. NATO wanted to build on this success. At the same time, it was

recognized that NATO support for Ukraine, in the form of arms and money, could

not continue indefinitely. A long drawn-out attritional campaign might hurt

Ukraine (with its smaller population) more and exacerbate recessionary trends

in European economies.

A single offensive which resulted in an unmistakable military victory as well

as shatter Russian morale was therefore the preferred option.

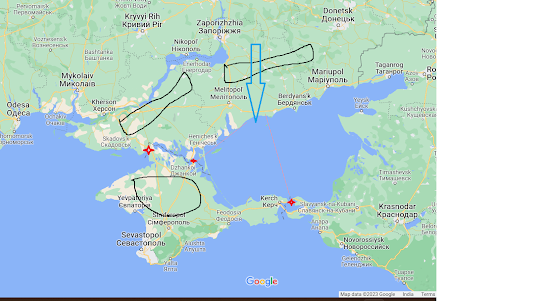

Crimea, Russian forces and the proposed offensive

The objective: As seen on the map, a thrust towards

the cost (blue arrow) to capture Berdiansk or Mariupol) would cut the land

bridge from the Russian mainland to Crimea. This would isolate 3 groups of

Russian forces (in black) who would have to depend on supply from the Crimea

rail/road bridge as well as ferries. However, Ukrainian long-range missiles

would be able to destroy the bridge and any ferries across the Kerch straits.

The narrow causeways connecting Crimea with the 2 Russian army groups - 8th

Army on the Eastern bank of the Dnieper) and 58th army to its East,

could also be destroyed. This would cut off the 3 Russian army groupings from

each other and from Russia.

This would lead to not only the loss of the 3 army groupings, but the recapture

of Crimea. It would not just be a catastrophic military defeat, but probably

cause Putin to be toppled – precluding the use of nuclear weapons to protect

Crimea.

Timing: The offensive could only start once NATO

equipped and trained 9 new brigades. This was in addition to units trained and

equipped earlier in the conflict. These 9 brigades were only ready in May, albeit

partly. Artillery ammunition, which I had touched upon earlier (part 2 of my

Ukraine posts) had to be surged and stockpiled. Ukraine had to separately raise

and equip the equivalent of 8 `storm’ brigades to replace losses in the battle

of Bakhmut that ended in May. After the spring thaw, the ground would also be

hard enough to allow for mechanized operations, only from May.

The Russians, who had mobilized 300,000 men from Sept 22,

had finished training them and started inducting them into frontline units.

They also spent the time between Sept 22 and May 23, building defenses along what

is now called the Surovikin line.

When an anticipated Russian winter offensive did not materialize,

it was believed that the Russian army had low morale and were incapable of

offensive action (and would not fiercely defend a difficult position). The

Russian capture of Bakhmut also played into this assumption as it was believed

that this was done by the Wagner group, not the Russian army and the Wagner

group, which took high casualties, was not going to be transferred to the

Zaporozhe front – perhaps Western intelligence had an inkling of the Wagner

group rebellion against Moscow, on 23rd June. I think it too much of

a coincidence that by 23rd June the Ukraine offensive was expected to either

reach the sea, or make a significant break in the Russian lines for a clear

path to victory to be visible and panic to set in among the Russian army

leadership.

The Russian view: Russia chose to consolidate in winter and build strong

defensive positions along the Zaporozhe front. Newly mobilized former veterans

were retrained, rather than pushed into battle, which is reflected in the low

casualty figures (about 3800 dead among 300,000 mobilized, as per Mediazone’s

detailed analysis). The battle of Bakhmut involved the exchange of Russian

convicts for a larger number of the Ukrainian army killed (much like Stalingrad

destroyed the best German formations before the battle of Kursk).

This situation was similar to the Battle of Kursk in 1943. The

Kursk bulge was too inviting a target for the Germans not to attack. The Red

army spent the spring of 1943 preparing for the attack. Hitler could not attack before July, as he

needed to wait for enough quantities of the new generation Panther and tiger

tanks and freshly inducted troops, much like Ukraine had to wait for NATO

weapons, which they thought would overcome deficiencies in aircraft, artillery

and manpower. In both cases, it was believed that a sudden attack by superior

armed and trained mechanized force, with better morale, would overcome a

prepared defense, as earlier experience suggested.

In 2022-23, The Russian army's war college prepared a paper on conducting a flexible defense which Russia is now demonstrating. The Lt. Gen who wrote that was then asked to command the Southern front, to implement his strategy.

The order of Battle (ORBAT).

Russia: The forces on the southern part of the front, were part of

Russia’s Southern Military command and comprised the 8th and 58th

Army.

The 8th Army was deployed along the

Eastern bank of the Dnieper, having withdrawn across the river in Sept 22. It

comprised:

20th Guards Motor Rifle Division (MRD) and

7th Guards Air Assault Division (with 4

regiments of 2000 men each).

The 8th army was supported by 2 artillery and two tank regiments.

The 58th Army. On the Zaporozhe front facing the expected

Ukrainian offensive. It comprised:

- 42 Guards Motorized Rifle division & 19 MRD.

- BARS-10 & 11. Each was a 5000 man brigade of volunteers.

- 1 Naval infantry and 1 tank brigade.

- 2 tube Artillery brigades and 1 rocket brigade.

There were also 2 battalion sized Spetsnaz or special forces units.

Holding units (part of Southern Military district): 2 Rifle brigades and 2 Donbass Militia Brigades.

Ukraine ORBAT

West of the Dnieper: 2 Tank and 4 rifle brigades, incl 1 of

the territorial army, in reserve.

1 Artillery brigade

Zaporozhe front:

9th Corps: 60th, 65th & 128 Assault Brigades

23, 59, 67 Brigades.

47, 31, 32 Mech brigades

43 Arty brigade

Of these 11 brigades, the 47th, 31st & 32nd

brigades were NATO trained and equipped.

Marine Corps: 33, 35, 37, 38 Marine Brigade supported by the 45th

Artillery brigade

The 33rd brigade was NATO trained and equipped.

Each marine brigade comprised 2000 men, so this was a 8000 man formation.

10th Corps: 116, 117, 118 Brigade.

82nd, 46th

71st Air assault

brigades

4 Battalions independent infantry (Foreign

fighters)

44th

artillery brigade in support.

The 117th, 118th and 82nd Brigades were NATO trained and

equipped.

There were also `holding formations’ meant to hold

ground in areas of the Zaporozhe front (half the 150km front) where Ukraine would not be advancing.

They were:

3rd Tank brigade (later redeployed to Kharkiv)

53 & 30th brigades

100, 102 & 108th territorial army brigades of low

quality.

Reserve brigades : 61st 115th & 21st brigades

& 3rd national guard brigade

The 21st brigade was NATO trained and equipped.

Map showing the units of Russia’s 8th and 58th Army and Ukraine’s 9th and 10th Corps and Marine Corps. The arrows were the planned axis of attack for the counter offensive

Of the 9 NATO trained brigades, 1 was redeployed to the

Bakhmut area before the counter offensive. Another, the 21st Brigade, was moved to the Bakhmut area after the counter offensive began. Thus while

Ukraine used all its 9 new NATO equipped brigades, 2 of them were not part of

the counter offensive.

The counter offensive would effectively be fought between

Russia’s 58h Army and Ukraine’s 9th, 10th and Marine

corps. Excluding artillery, there would be 10 brigades on the Russian side and

20 on the Ukraine side, with 4 more Ukrainian brigades in reserve. Ukraine had 6 `holding’

brigades vs. 3 for Russia. Russia would transfer 2 regiments of the 7th Guards Air assault

division to 58th Army, making the ratio of Ukrainian brigades to Russian as roughly 20 : 12

Along the Dnieper, both sizes were at roughly the same

strength. 6 Russian brigades (after the transfer of 2 regiments to 58th

Army) vs. 6 Ukrainian. The Dnieper river was a formidable obstacle to cross,

but if the Kakhovka dam was blown (which happened), it would be possible to

cross the Dnieper easily in some places, as Ukraine did (shown by the red arrow

across the Dnieper).

A glance at the map shows that it is easy for the Russians

to transfer units from 8th to 58th Army, since the

distance to be covered is low. On the other hand Ukrainian units trying to move

from West of the Dnieper to reinforce the counter-offensive would have to cross

the river and travel a longer distance, increasing the chances of interdiction

from air strikes.

Russian pressure all along the Eastern part of the front, would

make the transfer of Ukrainian units from the East to the Zaporozhe front difficult. This was exacerbated by Ukraine’s decision to start a new counter

offensive North and South of Bakhmut, that meant the transfer of reserves away

from Zaporozhe. Ukraine also transferred 2 reserve brigades to the Kharkov

front, to stop a Russian offensive there. In all, 5 brigades earmarked for the Zaporozhe

CO, would be transferred away. 1 of these before the counter offensive and 4

during.

The Ukrainian plan.

The counter offensive would start on the night of 4-5 June. 2 (each) Brigade

sized formations would make 4 thrusts across Russian lines. These would be made

by 9th Corps and the Marine Corps. The Russian defense of Zaporozhe,

comprised 3 defensive lines. It was expected that at least 2 of the 5 thrusts

would succeed in breaking the first 2 Russian lines, after which 10th

Corps would exploit the breakthroughs, in the sectors they occurred in, beat

back any Russian counter attack and reach the coast. The assumption was that it

would be over (in terms of a decisive breakthrough of Russian lines), by the

end of June, after which dissatisfied Wagner forces would move on Moscow.

An additional opportunity was presented by the destruction

of the Kakhovka dam – my view is that repeated shelling caused a weakness in

its structural integrity. This made crossing the Dnieper easier and weakened

Russian defensive positions along the Dnieper bank.

If the Ukraine CO resulted in a panicky retreat of the Russian forces, it could

be exploited by a Ukrainian force crossing the Dnieper.

The composition of Russian defenses was well known. As

suggested by analyst Lt Col Scott Ritter, simulations of the counter attack

would have been carried out by NATO, even to the level of individual sections

(8-10 men). One can predict for e.g.

what damage a 155mm barrage will do to an infantry section that is dug is and

at what point that unit will break and retreat, or flee. A simulation with a

force ratio of 20:12 would typically need the following pre-requisites for

success:

- - Air superiority.

- - Attacking side is better in operational art (or

Combined arms warfare) than the defenders. It was

assumed that NATO training will ensure this – as compared to conscripted

Russians.

- - Artillery (or firepower superiority) of 3 :

1. After stockpiling shells, Ukraine had

rough parity with

Russia in both guns and the number of shells each had in stock.

- - Domination of electronic warfare and

intelligence.

If there was any doubt about the timing and location of the

CO, the Ukrainians dispelled it by announcing it on every medium of

communication (apart from leaked `Pentagon papers’).

On the Russian side, use of drones was almost 10X higher than the previous year

(as seen from the number of verified strikes by Lancet drones) by Ukrainian

drone effectiveness was greatly impacted by superior Russian jamming. The

Russian air force had increased its sortie rate, partly because its KA-52

attack helicopters were equipped with longer range anti-tank missiles (outside

Manpad range) and superior electronic warfare systems and because the Ukrainian

air defense network had been greatly degraded in previous months.

Phase 1: 4 -30 June. The first phase of the CO was a disaster which NATO also admitted. In the first week 20% of NATO supplied equipment was a confirmed loss, reaching 33% after the first 15 days. This meant an over 50% loss in equipment in those formations actually fighting, since 10 Corps had not yet been committed. The loss in manpower would be proportionate to this, particularly as it was mines (not artillery) that was believed to have caused the largest share of casualties. The claim of 50% losses in equipment among the brigades used in phase 1, can be confirmed from verified losses recorded by Oryx. For e.g. 51 of 99 Bradley IFVs were confirmed to have been lost. However, the brigades committed to the CO in phase 1, had 60 Bradleys, which is a greater than 50% loss rate. A similar loss rate was seen in the brigade equipped with Leopard tanks. I believe the presence of Germany’s Leopard tanks did more to boost volunteers to the Russian army, than any initiative of the Russian govt.

13 Brigades with 2 artillery brigades were committed in phase 1, in 5 thrusts

covering 70 km of a 150 km (as the crow files) Zaporozhe front. They failed to

make any progress in 3 of the 5 thrusts and marginal progress in 2 (but falling

short of the first defensive line).

9 of the 13 brigades suffered very heavy casualties. The 31, 32, 35 & 37th

Brigades disappeared from the order of battle till date (moved to the rear, to

be refilled with freshly mobilized men).

What was left of the 67th

brigade was redeployed to the Northern front. Of the remaining brigades,

Russian MoD announced that the 30th, 59th, 60th

and 65th brigades suffered more than 400 irrecoverable casualties

each. This seems a credible estimate as 85% of casualties announced by the

Russian MoD are not identified with units. If they are, it tends to be based on

a higher level of probability. Interviews with fighters done by Pro Ukrainian

media, also points to a very level of casualties among brigades in phase 1.

The high casualties and failure to achieve any of the phase 1 objectives, led

to the following, which were an admission of the failure of phase 1.

Ukraine started a fresh counter offensive north and south of

Bakhmut. They initially made some progress – largely because the Russians, who

had only occupied the area in Apr-May, did not have the time to prepare

defenses. However, at the time of writing, the Russians recovered most of their

lost territory (particularly in the Klisheevka area). Apart from using 1 of

their new NATO trained brigades in the earlier battle for Bakhmut, Ukraine also

moved the 21st brigade to the Bakhmut front.

Among the brigades in defensive (holding) roles, Ukraine transferred the 3rd

Tank to the Kharkov front to stop a Russian advance. This was done despite the 30th and 53rd

brigades taking heavy casualties in the attritional fighting in previous

months. It leaves Ukraine dangerously exposed to any Russian attack in sectors

that were hitherto not threatened.

Among the reserve brigades, Ukraine moved the 115th Mechanized and 3rd

National guard brigade to the Bakhmut front. This was a tacit admission that

the CO was not working and its brigades might achieve better results, either in

taking territory in the Bakhmut area

(failed), or stopping a Russian advance towards the Oskol river (which

has been a partial success as of 27 Aug). This leaves the 61st

brigade as the only theatre reserve for Ukraine. As of 28 Aug, its whereabouts were unknown.

From the elite 10th Corps, the

46th brigade was committed in June itself and took heavy casualties.

A raid across the Dnieper failed when the attacking force

took very heavy casualties, without tying down a lot of the Russian defenders. It enabled the Russian army to transfer 2 of

the 4 regiments of the 7th guards Airborne division to the more

threatened Orekhov sector of 58th Army.

The commander of the 58th Army, Gen Popov, was

fired after he complained (indirectly to a former General and now a Member of

Parliament) about the lack of rotation for his men and shortages in artillery

and counter battery radars, leads me to assume that the Russians did not deploy

reserves in phase 1 and that they did not have the advantage in artillery they

had traditionally enjoyed in the war.

The ORBAT of both sides, shows a book strength in guns and rocket launchers

that are similar. NATO had stockpiled ammunition that would in theory ensure

that the shells allotted, per gun per day, would be similar to Russia’s.

Of the 4 axes in which Ukraine attempted to advance, there were some advances

in 2 of them – in the Rabotino sector and at the Vremievsky ridge. However, in

neither case did the Ukrainians reach the Russian first line of defense. The

area occupied was largely `grey zone’ not fully under the control of the

Russians and where there was no serious defense.

Phase 2: 2nd week July – 1st

week August.

In the latter part of phase 1 Ukraine changed tactics and the new tactics would be used throughout phas 2. There would be fewer armored vehicles (to reduce high losses) and instead smaller groups of men would infiltrate into Russian lines in a slow advance. While this reduced vehicle losses, it increased human losses and reduced any chance of breaking Russian lines, because any penetration would be sealed off and taken in a counter attack, or destroyed by artillery.

There was an attempt to show progress in the CO before the NATO summit on 11th

July, which failed.

In phase 2, the intensity of the CO reduced - as seen from reduced casualty

claims form the Russians – and reduced

daily death toll reported by independent media and no significant claims of

capture of territory by the Ukrainian media. There was more focus on Ukraine’s

other counter offensive, North and South of Bakhmut. By the end of July, that

offensive had fizzled out, though heavy fighting continued and there remained a

strong Ukrainian presence in that sector.

There was also a Russian offensive in the North, aiming to reach the Oskol

river and Kupiansk. Stopping it required Ukraine to move a reserve brigade and

the 67th Brigade of 9 Corps, from the area of the CO, to the

North.

Ukraine did make further progress in both areas they had moved into in phase 1

– towards Rabotino village and towards Vremievsky ridge. The capture of the

village of Staromayorskoye was the first setback the Russians had. While the

village itself had no strategic value (surrounded on 3 sides by a higher ridge)

it was a springboard to capture of the more important village of Urozhayne,

which would have given the Ukrainian marine corps more scope to maneuver around

Russian defenses.

The Russians identified Rabotino and the Vremievsky ridge as

the main effort for Ukraine. As per doctrine their reserves started moving to

both areas. 2 Regiments of the 7th Guards airborne division and a

brigade of BARS (volunteers) moved to Rabotnio, while a Naval infantry brigade

moved to the Vreminsky ridge.

At the end of both phase 1 & 2, Ukraine had the option of calling off

the CO and saving valuable NATO equipment and trained manpower from a battle of

attrition they were not winning. The battle of Kursk was called off by the

Germans when they were in a better position than Ukraine’s. The `sunk cost’

fallacy could have affected Ukraine’s thinking, along with the feeling that `one final

effort’ could win the battle. It was similar to Germany’s thinking at the gates of Moscow in Nov 1941, when

military logic dictated that the Germans should have dug in for the winter

outside Moscow, but it was felt that

the `last unit' thrown into battle would bring victory, because the Red army was in worse shape. The Germans had the same view at Stalingrad a year later.

Phase 3: 1st week August – Current

Ukraine attempted to exploit their gains in both Rabotino and the Vremievsky

ridge. They captured the village of Urozhayne, but this was either recaptured

or in the grey zone (under control of neither side) with the surrounding

heights being under Russian control. The Marine corps were too weak to exploit

their gains. They had brought back regiments withdrawn after phase 1 fighting,

but after Russia sent in reserves, to seal the gap in their lines and recapture

some lost ground, Ukraine had no numerical superiority in this area. Ukraine

recalled the 35th and 37th Marine brigades that were

withdrawn after phase 1. The Ukraine forces at Urozhayne are too small to advance further and are still short of the first Russian defence line.

Ukraine recognized the Rabotino was the only remaining

thrust that could be exploited. The whole of 10 Corps was sent to the Rabotino

area. The village was captured after the fiercest fighting of the CO to date.

It also changed hands, which was contrary to doctrine, which required

them not to contest territory in front of a defensive line and to fall back if

the cost of defending a position was too high. This tactic of fiercely contesting the `crumple' zone in front of the first line of defense was a new innovation from traditional Soviet and Russian defensive doctrine.

Ukraine’s last uncommitted brigade the elite 82nd airborne (named

after the US division with the same name) was sent to Rabotino, along with the

rest of 10 Corps and the 47th and 65th brigades of 9

Corps, recalled after phase 1. Ukraine also sent in the only new unit it could

find, the 15th National guard brigade and mentioned 10 brigades that

were involved in the capture of Rabotino. Subsequently,

10 Corps reached the first Russian defensive line south of the village, where they

were halted by

Russian counter attacks. Since this was the only Ukrainian effort – along a

very narrow front, any

advance by Ukraine without strengthening the flanks, would result in a

dangerously long salient, liable to being cut off, or attacked from 3 sides.

All Russian reserves – 2 regiments of the 7th Guards Airborne, 2

BARS brigades (10 and 11) and a newly arrived rifle brigade from the Far East,

were sent to Rabotino.

Thus 10 Ukrainian brigades in Rabotino, will find it difficult to make any

further breakthrough against 8 opposing Russian brigades. The conundrum for

Ukraine is that the harder they try to breakthrough, the more losses they will

take and any further advance harms their position (lengthening salient with a

small base pushing against increasing larger forces). It was a similar

situation to that of the SS Panzer Corps in Kursk 1943, when they made a

breakthrough and seemed to have won the critical battle of Prokhorova, but

retreated because of a similar situation as Ukraine’s 10 Corps (which has not

defeated the Russians in any set piece battle) finds itself in now. The Ukrainians cannot remain in place, because they do not have enough ammunition for extended combat.

It has been acknowledged by the Western media that the 10

Corps and the theatre reserve 61 Brigade, represent Ukraine’s last

reserves. There are no further units available anywhere, barring undermanned

and under equipped territorial army units. Russia, on the other hand has around

(as per Ukraine) 100,000 men in reserve along the northern (Kharkov – Kupiansk)

front, which is of less strategic importance than the Zaporozhe

counter-offensive. This figure seems credible, since we know these man have

been mobilized and trained (after considering replacements into existing units)

but do not feature in any of the units currently fighting - as I have explained

in part 1 of this Ukraine blog. If Russia needed more reserves in the

South, they can tap into this source, or move the experienced 150th

Rifle division, which is part of 8th Army and was moved to the

Bakhmut front. It can ideally get back to its parent formation, while new

brigades (located closer) can move into Bakhmut.

If Ukraine goes on the defensive, Russia has an opportunity to conduct its own

offensive, either in Sept, until the Oct rains, or in winter after the ground

freezes. The Sept-Mar period will be when Russia is strongest relative to

Ukraine’s manpower and armaments. After March, Russian production of key items

will equal consumption (assuming Russia conducts defensive operations only).

a lot of the thinking to me from the West governments , they seem to lack 2nd and 3rd level stratagies . I often wonder at their statements and decisions and wonder if there are any adults in the room.

ReplyDeleteclearly at this point in the conflict one would hope another plan would be devised , and yes one that included a peace deal that you actually have Russian involvement - although I doubt anyone in charge in Moscow would beleive anything the West said.

There seems to be an assumption that if Putin goes then their would be a civil war that could be exploited . However reading some of whats been said on that theres a fair possiblity that Russia would unite behind an even more radical leader.

a good summary though , I hope to read more in future , thanks.

Forbin

Pretty detailed, unbiased, reasoned analysis.

ReplyDeleteRespect for the work done. Thank you.

From Siberia.

Thanks. I have wonderful memories of my travels in Siberia 20 years ago !

DeleteGreat thought has gone into this. Lovely. Its amazing when will the West take their heads out of the sand? Seems like when they come out, they will say- Oops, where did Ukraine go? Regards.

ReplyDeleteThat is a problem when people believe their own propaganda.

DeleteFurther, I am thinking, in future when historians will look back at this meat grinder, I am sure they will bang their heads against the wall, thinking which kool-aid their ancestors were drinking?

ReplyDelete